Forgiveness: The Key to Overcoming Polarization?

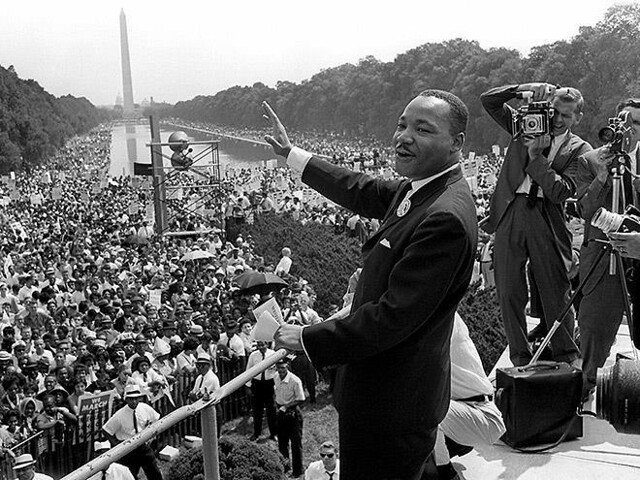

“Forgiveness is not an occasional act, it is a permanent attitude.”

Martin Luther King Jr. from his sermon, “Love in Action” (1962-1963)

As I write this we are preparing our bags to fly to Egypt to share, with some trepidation, the short animated film we produced with Coptic Christian iconographers and other artisans called The 21. Yes, it is the story of the 21 martyrs who were beheaded by ISIS in 2015, but it is fundamentally the story of faithfulness and forgiveness.

The film will be released to the public over the weekend of February 14-16, but if you are interested in hosting a screening for a small group, you can sign up here and view the film and materials that will be available with it. In addition, if you are in the DMV, you can join us at St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Church in Fairfax for a screening on February 15 on the 10th anniversary by registering here.

My trepidation comes from the thought of sharing the film with the martyrs' families and widows. Will it appropriately honor the martyrs in their eyes? Will they be enriched in their faith? Will it bring back grief? Or will it give them joy seeing not just the martyrs’ steadfast faith, but being reminded of the forgiveness that they all (including the families) communicated to their murderers?

Forgiveness. It is not our natural response to being wronged. It is, however, the key to our wellbeing, both personally and culturally.

I was reading about the horrific acts of revenge taking place in Sudan now, with over 150,000 people killed in ethnic and tribal conflict, largely out of the eye of the international community. This is our human history.

It does not have to be this way. My friend, filmmaker and fellow Wedgwood Circle board member Laura Waters Hinson produced the documentary As We Forgive about two Rwandan women coming face-to-face with the men who slaughtered their families during the 1994 genocide. Inspired by Christian teaching, Rwanda pursued the radical notion of reconciliation and set into motion one of the most powerful counter-narratives in modern times.

I was on the campaign trail in Lancaster, Pennsylvania with my former boss, Rick Santorum, when the horrific murder of 10 young girls in an Amish schoolhouse took place. We participated in a hastily put together service that evening, and heard one single word from the community: forgiveness.

Perhaps we are at a time in our country when the cultural carnage left by polarization needs to be overcome by forgiveness. As Jesus said, the first commandment is to love God with our whole heart, and the second is like unto it: to love our neighbors as ourselves. We have not done this well, much less loved our enemies, as Jesus later commands in the Sermon on the Mount.

I was reminded of the importance of humanizing our political rivals, and putting down our rhetorical swords with the eulogy read from former President Gerald Ford at the recent funeral of President Jimmy Carter. Bitter rivals, Presidents Ford and Carter forged a friendship on a flight to the funeral of Anwar Sadat in Egypt, and each agreed to write a eulogy to be read at the others’ funeral. This began a lifelong friendship.

For us to overcome our tribal disagreements, or at least to navigate them in a more healthy way, we need to also put down our rhetorical swords, choose to humanize our opponents and if wronged, forgive them.

As John Hopkins points out in a summary of research, “studies have found that the act of forgiveness can reap huge rewards for your health, lowering the risk of heart attack; improving cholesterol levels and sleep; and reducing pain, blood pressure, and levels of anxiety, depression and stress.”

As Ford and Carter understood, the rhetorical barbs thrown at one another during the campaign had wounded each deeply. We like to think that sticks and stones may break your bones, but words will never hurt us. But the Apostle James knew better, and called the tongue in 3:6 “a fire, a world of unrighteousness. The tongue is set among our members, staining the whole body, setting on fire the entire course of life, and set on fire by hell.”

As Gerald Ford said about their relationship,

“We immediately decided to exercise one of the privileges of a former president – forgetting that either one of us had ever said anything harsh about the other in the heat of battle.”

We need more models of political and ideological rivals who show us how to tame the tongue, agreeing to disagree agreeably. One of my favorite road shows is that of Princeton professors Robert George and Cornel West, who could not be more different ideologically, but share a faith and respect for one another’s firmly held convictions.

Robert George and Cornel West

It was refreshing to see President Trump playfully poke President Obama at the Carter funeral. If he allows this generous side of him to overcome the human instinct to seek revenge, President Trump will be more at peace, and so will we all. As he said about their interaction, “We just got along. But I got along with just about everybody.”

Trump and Obama conversing at Jimmy Carter’s Funeral

President Trump gave hints of this in his inauguration address with a call to national unity and common sense, although his playfulness was absent and his words at times harsh. Some say after his near-death experience President Trump is a changed man. Based on the inaugural comments he made and executive orders he signed, he may be more resolute than ever in what he believes and what he feels called to do. The question is, can he change the way he treats those who differ with him? As President Lincoln invited the nation at his second inauguration:

"With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

President Lincoln, March 4, 1865