Wilberforce’s Two Great Objects

In June of 2024, we launched Salt and Light Stories as a creative experiment. The graphic novel tells the stories of modern day “saints” through mini-comic series, a medium increasingly familiar to Gens Z and Alpha.

As 2024 came to a close, we wrapped up our fourth completed mini-comic, Guinness: Brewing Good. From the stories of Guinness, Daniel, and Larry Norman, to reflecting on our namesake, the Clapham Sect, we’re grateful for the opportunity to share these inspiring tales through creative storytelling.

To kick off 2025, we’re excited to introduce Wilberforce’s Two Great Objects, a follow-up to our previous series, How Fierce Convictions Led to Amazing Grace. This new series continues the story of the Clapham Sect, a group of social reformers in late 18th-century England, focusing on two critical issues William Wilberforce and Hannah More worked tirelessly on together—issues referred to as Wilberforce’s “Two Great Objects,” drawn from his 1787 journal entry.

“The image I used is based off the medallion that was produced during this time in support of abolition. It's such a powerful singular image that I thought it deserved to have a modernized, digital version of it.” -Wade McComas, Illustrator

In a recent interview, Clapham Principal Mark Rodgers sat down with author Kevin Belmonte to discuss these two influential individuals. Kevin, a two-time finalist for the prestigious John Pollock Award for Christian Biography, is the author of William Wilberforce: A Hero for Humanity, which won the award in 2003. He also served as the lead script and historical consultant for the acclaimed film Amazing Grace. Kevin’s most recent work is a biography of Hannah More, titled The Sacred Flame.

Today we’ll share a piece of that interview in this newsletter as a preview, and over the coming weeks we’ll be sharing excerpts from this insightful interview on the Salt and Light Substack. To begin, Kevin Belmonte reflects on Wilberforce’s early life and faith journey.

Mark Rodgers

Well, thank you for doing this, and congrats on the Hannah biography.

What drew you into the life of William Wilberforce that motivated you to write a biography about him, and what year was it when you wrote it?

Kevin Belmonte

2002, I'll walk you through that. It's a kind providence, really. Flashback to 1983; I'm 19 years old. I went to go hear Francis Schaeffer speak, and went down to Massachusetts to a community college – he was speaking there. Very important. I had read all of his books, and I was excited about that. But what surprised me, and where the kind providence comes in, is someone was handing out copies of a very short lived publication called the New England Correspondent. And there was a lead article in there about William Wilberforce and the Clapham Circle. And I picked it up and read it, and I thought, I've never heard of these people. And that planted a seed of curiosity. I mean, I read the whole article. I was absorbed. I learned about the Abolition of the Slave Trade, how the fight was fought for 20 years against so much opposition in Parliament, not just by Wilberforce, who was the point person, but by a circle of very talented people, sort of a cabinet of philanthropy, if you will. People who were very gifted, who concerted their talents. And the story really captivated me.

And when I was in college, I mentioned it to my history professor, and he was sort of dismissive. He said he knew who they were, but, you know, it was really just a general Enlightenment era impulse that led to all that, and Wilberforce and all those folks weren't that important. And I remember thinking at the time, I just don't know if I agree with that, and so I had a chance to revisit all of that in grad school and do a project for my church history class, and my professor was so taken with it, he said, “You know, Kevin, you really ought to think about doing a master's thesis on this.”

Move forward just a little bit. I met Os Guinness in 1994 – I was corresponding with Chuck Colson. Wilberforce was a great light for them. I sent them copies of my master's thesis, and that was the genesis of my book. It ended up taking a little longer to get across the publishing finishing line than I expected – 2002 – but the Lord was in the details, because my knowledge really needed to grow. It was a deep dive into British government, British culture, for understanding all the facets that led to that incredible movement, that ‘concerting of benevolence,’ as Wilberforce used to call it, to abolish not only the slave trade, but to set in motion all these philanthropic initiatives that helped foster a good society. So, that was the way in. It was something I never really saw coming, and it happened when I was young, but I was very grateful.

Mark Rodgers

That's a wonderful story. I think you know – I know we shared this when we first met – but my timeline is very similar. I first heard about Wilberforce when the pastor of our church in Pittsburgh, John Guest, gave a sermon in 1984 on Wilberforce – based on a book he just read that Os Guinness had given a talk on – Garth Leans God's Politician. And that sermon in 1984 is what started me on my trajectory. So, we have a very similar time arc of our own vocational lives and our interest in Wilberforce.

Well, as you kind of look back at that amazing story of his life, I'd love for you to share one anecdote of what you believe was the origin and seed of faith? Where did his faith come from, that eventually he had to recover later in his life? Because, we covered this in the last comic series. Where did that initial faith come from in his own life journey?

Kevin Belmonte

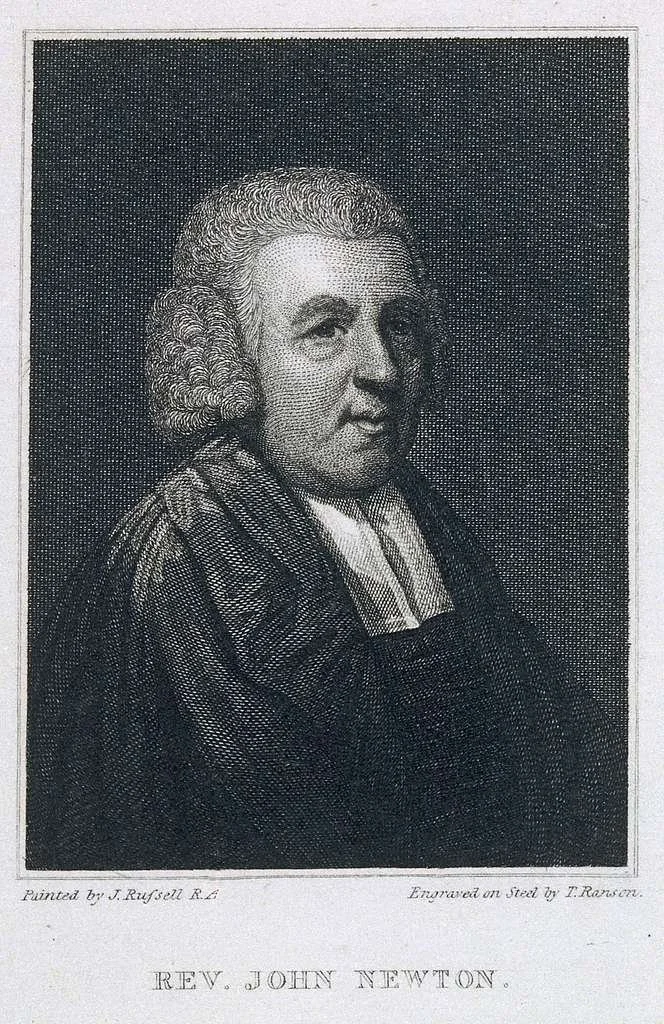

He was really born of tragedy; Wilberforce suffered a great deal of personal loss in his immediate family when he was young. His father died when he was eight years old. He lost a sister, and then a few years later, another sister. For a time, his mother was subject to what they called a long and dangerous fever. So, this all happened in a tightly focused window of time. He was sent to live with a childless uncle and aunt in Wimbledon, and they were great friends with John Newton.

Young William Wilberforce

And when I was working through the script arc for [the film] Amazing Grace, we were teasing this out, because you really can't make this sort of thing up. The idea that he would have encountered John Newton as a child, would have heard his stories of the sea, and, of course, the great redemptive story that we know is realized in the hymn “Amazing Grace,” come to reverence Newton as a parent, but then all of a sudden, when his mother recovers and Wilberforce, to all appearances, embraces the faith that was modeled for them in this setting.

His mother goes right down to London. She wanted none of this. She was all about dynastic ambitions for her son. They'd had members of the family who were politicians, and perhaps young William might take the family fortune and parlay that into a seat in Parliament. There were hopes for him that had no room for what they called “Methodism” or “enthusiasm.”

So, he was taken away from that situation, and by the time he went up to Cambridge, they had set about ‘scrubbing his soul clean of Methodism’, I think was the phrase. And he said, “I was just as thoughtless as anybody.” By the time he went up to Cambridge, he met William Pitt, the future prime minister, there they became fast friends. They attended debates in Parliament, and they both set their sights on getting a seat in Parliament, and they did it at an incredibly young age.

William Pitt

I mean, Wilberforce was just shy of being 21 when he went out on the hustings and stood for Parliament, and he was worried that the election would be called too soon, and he wouldn't have turned 21 to be old enough to sit in Parliament. So, it all worked out well in the end, and he actually got there before Pitt, who was the great rising star, becoming Prime Minister at 24.

William Pitt and William Wilberforce (from the film Amazing Grace)

The world was sort of his oyster at that point. I mean, he could have had any seat in the cabinet he wanted, if he'd asked for it. He became a very powerful member of Parliament in his own right. In 1784 when he won the seat for the entire county of York, one of the most powerful seats in the legislature, he went on a tour of Europe to sort of savor the sweets of that victory. And lo and behold, he reconnects with someone from his youth who was also an Evangelical, Anglican Isaac Milner. By the time he returns home, he's in the throes of a spiritual crisis, because he realizes that the faith he thought he'd once set off to the side from his youth had never really left him. He'd set it aside. But God wasn't done with him.

He got back to London, you know, a dark night of the soul kind of experience. Didn't know who to reach out to, and he remembered Newton, and you have this picture of him walking around the square outside Newton's home, trying to muster up the courage to go in, because you had a feeling, or at least he did: “If I go through that door, everything I've worked so hard to achieve might be at risk.”

All of the the the skepticism, the scandal, the prejudice that he'd known when he came out as what they called a “Methodist” back then, or an “enthusiast,” that might be laid at his feet again, and he has this meeting with Newton, and it's absolutely pivotal, because coming out of that meeting, Newton told him he'd never stopped praying for him, and that he had hopes someday the Lord would bring him back to that first love, that faith that he cherished as a child, and when he came away from that meeting that circle was complete, he had that reunion with faith.

And you fast forward a couple of years now, as a person of faith, he's looking for something, a cause, really, to make his own in Parliament, something worthwhile, something born of faith, something that can help make the world a better place, a return for what had been given him. And we have this wonderful meeting that takes place in October 1787, with Newton. And they talked about the slave trade. Of course, Newton had been a former slave ship captain, and he was consumed with grief and remorse over that chapter in his life. He knew Amazing Grace had saved a wretch like him, but he too was thinking that perhaps I have this young friend in Parliament, maybe I can give evidence against the slave trade I once served, and maybe we can set about trying to get rid of this.

John Newton and William Wilberforce (from the film Amazing Grace)

That's really where things came to a head, at that pivotal point. And it's just remarkable, because, if you think about it, so many times when we set something aside as young people, we never come back to it. It's just a source of too much pain for Wilberforce, it was caught up with the death of his father and then the back and forth between his mother and his uncle and aunt. It was a painful time, and some people just never want to revisit that – it's a wound too tender to touch.

But though he had suffered as a young person, Newton was the perfect person for him, because Newton's own stormy story had been so stormy and so fraught itself. He was the perfect person to understand how a young person was casting about not only to have a reunion with faith, but to try and find a life calling and purpose. He really helped steady and mentor Wilberforce, and he gave this crucial bit of advice – many evangelicals, then, if they had a serious encounter with faith, tended to withdraw from culture – and Newton said just the opposite.

He told Wilberforce, you stay where you are in Parliament. It may be that for such a time as this the Lord has put you where he has put you; you may have the opportunity to do as Daniel did way back in Old Testament times, and be someone who is close to the seat of power, who can make a difference for good. And so, you know, it's a remarkable thing, because if you fast forward 20 years beyond 1787, Newton lives just long enough to receive the news from Wilberforce that the slave trade he once served has been abolished. And I remember talking to Steve Knight, the screenwriter for Amazing Grace, about this. And I said, this might sound contrived and a bit too fantastic, but that's the way it really unfolded. So, it's a remarkable story, and Wilberforce had a phrase that I love to cite. He said, “A gracious hand leads us in ways that we know not.” I just think about that all the time.

Mark Rodgers

That's beautiful. And I want to move to Hannah More now, but I want to just acknowledge that you and I both share an origin story for the film Amazing Grace. And those of you that are listening to this, watching this, or reading, if you haven't seen the film, we would encourage you to – it's more challenging than it should be to find. It should be a lot easier to get hold of, and hopefully, maybe technology will release that. But one of the funny things about that film, and you can't really see it in the room behind me, but the poster from the film, you know, that displays in the theaters, you know, boldly lists the main actors.

There's only one that's not listed on the poster, and that's an actor named Benedict Cumberbatch who played Pitt, a fairly major character in the film. At that point he was a largely unknown actor and hardly even mentioned in the promotional materials of the film. Of course, now he would be the person given the most headlines in terms of celebrity. A remarkable film. I urge readers to see it.

Now, when we first met, I think, or maybe early meetings, we were in a retreat center on the eastern shore, and you handed out for everybody a photocopy of Wilberforce’s diary entry of Wilberforce’s in which he lists his two great objects. What you gave me is right here behind me on the wall. My wife framed it, and that's the copy that you gave us 20 years ago now, Kevin.

The two great objects were the end of the slave trade, which we've discussed, and the reformation of manners, and we'll talk about next. The Clapham Group were all collectively involved with these two great objects, but Hannah More uniquely shared in Wilberforce’s commitment to them, especially the reformation of manners. So, let's talk about Hannah More next.

We hope you've enjoyed this interview and a preview of what’s to come in the next several weeks. We invite you to join our grand experiment by subscribing to our Substack, where you’ll receive new pages of our comic every Wednesday and a short reflection essay every Friday—completely free. Be sure to follow us on Instagram for exclusive sneak peeks of unreleased pages and exciting updates. We’re thrilled to continue sharing the stories of those who have inspired and impacted us.